Instead of looking for hope, look for action.

—Greta Thunberg

Then, and only then, hope will come.

We’ll be less activist if you’ll be less shit.

—School Strike 4 Climate placard

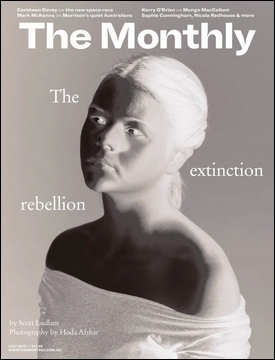

Bourke Street Mall in central Melbourne is strewn with hundreds of bodies. Shoppers edge past the spectacle trying to work out what’s happening. Police stand at a watchful distance. Commerce in and out of department stores is postponed behind this cheerful shambles of banners and placards, megaphone speeches and sea of sprawled corpses of the theatrically dead. Many of the flags and cardboard signs bear a stylised hourglass in a circle. Weeks after thousands of people brought central London to a standstill under this banner, the Extinction Rebellion has come to Australia.

It is less than a week after the stunning re-election of the Morrison government. People were calling it a “climate election” and the phrase caught on. A campaign shaped in part by the drought, the dying reef, Adani’s Carmichael mine and the politics of coal. For some, a major United Nations report on planetary extinction weighed on their voting decision. For those in more of a hurry, there were spicy memes of Morrison and Barnaby Joyce touching up a piece of coal in the House of Representatives. Against a rising tide of climate awareness, surely these tone-deaf antics would be an electoral liability.

Not so much. Well before the election-night count was even finished, Resources Minister Matt Canavan had fired off his euphoric all-caps tweet: “START ADANI!”

For many, shock turned rapidly to bitterness. “So your side lost? Just accept it gracefully,” an opinion piece in The Sydney Morning Herald advised in the aftermath. A plea for “civil discourse” rose amid furious finger-pointing at Queenslanders, boomers, pollsters, Bob Brown, someone, anyone. Canavan’s tweet cut through this clutter louder than a hundred opinion pieces. You had your climate election. Coal won. Deal with it.

For some, the outcome on May 18 didn’t inspire graceful acceptance. With trepidation, I’ve asked Nyah Shahab how she felt in the wake of the 2019 election.

“Very, very angry. I was sad at first, but then I realised I can’t really make viable change with sadness. So I manifested that into anger.”

She is midway through Year 12, a year that I dimly recall being as stressful as hell, since I’d been told by teachers, parents and peers that how well I did would shape the rest of my life. But those among Shahab’s generation understand that the rest of their lives will be shaped by something profoundly more threatening. And so, in her final year of high school, she has been a core organiser for the School Strike 4 Climate movement.

“I’m juggling it because I don’t think I have any other choice,” she says. “If climate change continues to happen it’s my future down the drain.”

The first large-scale School Strike 4 Climate action took place in 2015, at the time of the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris. The idea then lay mostly dormant until a 15-year-old Swedish student by the name of Greta Thunberg reignited the movement in August 2018, taking each Friday off school to demonstrate on the steps of Sweden’s parliament. Thunberg, who’d been inspired to action by the student-led gun control movement in the United States, had a simple demand: that her government immediately bring energy policy in line with the imperatives of scientific reality.

Somehow, this small but unyielding action hit a nerve, and school strikes took off around the world. Young Australians were among the first into the streets, with thousands joining the call by three students from Castlemaine, central Victoria, in late 2018. By March 2019, more than 1.6 million students were striking in more than 2000 cities worldwide. Their movement has provoked support from climate scientists, senior politicians, diplomats and the secretary-general of the UN. More importantly it has changed the terms of the debate, and has prompted a new kind of conversation.

As one of the MCs of the Melbourne event, Shahab recalls looking out at the tens of thousands of young people and their supporters, and realising what they’d done.

“Maybe people aren’t changing yet, but they know that’s what we want, and we’re willing to rally in the thousands, almost millions, globally. That’s pretty awesome – seeing the impact we’ve had on adults specifically.”

The extinction rebels on Bourke Street have made their point; there will be no arrests today. For participants, it is a vital show of defiance and determination, a chance to regroup and find strength in one another. Miriam Robinson, who has worked on Galilee Basin coal campaigns in Queensland, has taken up the mantle of Extinction Rebellion organiser.

“The time’s right,” she tells me. “Up until now a lot of people were thinking it’ll be okay, it’s a long way off, or the UN process was going to work, maybe our governments are going do something. I think the realisation is dawning now that they’re not. To quote Greta Thunberg, no one is going to come and save us. We have to pull the emergency brake.”

Is this really how social change gets done, or is this group of people just taking out their frustrations in public because “their side” lost an election? Even if you agree with them in principle, wouldn’t they be better off working through formal channels to make their case to the people who make decisions? After all, for those stuck on a tram waiting to let a demonstration through, the inconvenient truth is that traffic jams suck, even if they’re for a good cause.

It is clear to those organising these actions that formal channels have failed. Elections work as a social pressure release valve; a periodic reset of pent-up political stress. They’re an alternative to guillotines in town squares; a reluctant concession to the working poor who in times past rejected graceful acceptance of corrupt monarchies or feudal dictatorships. But the darker the skies become, and the more our representatives refuse to take steps to keep people safe, the more the political pressure will build.

Collective organising – even if it means breaking the laws written to protect the powerful – has always been part of the repertoire of dissent. In this part of the world, Aboriginal people have resisted violent dispossession, extinction and destruction of landscape for 23 decades, by way of raids and strikes, sit-ins and marches. There still isn’t a wide appreciation of just how deep the lineage of resistance goes, even though this unbroken continuity of defiance predates the “modern” environment movement by 200 years.

“The amount of civil disobedience that has taken place over 231 years – it’s extraordinary. I wouldn’t be here today unless my own family, my own mob had been engaged for that long,” Jai Allan Wright tells me. A young Yugambeh man from south-east Queensland, Wright is a volunteer organiser with the Seed Indigenous Youth Climate Network, which is affiliated with the Australian Youth Climate Coalition (AYCC). He is driven, in part, by the desire to offer something more than just resistance.

“What Indigenous Australia can do when we’re given the freedoms to practise what we need to do to protect land and country and culture, when we can get back to our practices, to have healthy communities, and be able to reach our potential as people, we can start to bring some of that knowledge, and our own healings, back into the world. We can start to dissect these patterns of destruction and self-destruction.”

In this wider perspective, measurements of the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere represent just one critical symptom of the deeply maladaptive economic and social structures we’ve inherited and are busily perpetuating. Adani’s proposed Carmichael mine, Clive Palmer’s proposed mine right behind it, Origin Energy’s stunningly polluting fracking plans in the Northern Territory, Equinor’s oil ambitions in the Great Australian Bight – these are all different tentacles extending from the same underlying superstructure. Simply erecting vast swathes of solar panels won’t solve the world’s brutal wealth inequality, and it won’t give Wright’s family the power to determine what happens on their land. Nor will it stop the old-growth forests falling to feed offshore pulp mills, or the oceans from filling up with plastic.

In May 2019, the AYCC’s campaigns and communications director, Kelly Albion, raised concern at the promotion of top-down or “emergency” solutions to confront the systems and structures that are driving the climate towards a tipping point. Albion suggests framing the campaign as one of climate justice, centred around those who have spent their whole lives on the frontline.

“Climate change is not a simple problem to address, because it is caused by the most complex system of powers – capitalism, white supremacy, colonialism and the patriarchy. We can’t ‘fix’ climate change but we can set up fair and just systems to respond.”

Globally, the canon of nonviolent resistance calls up images of Gandhi’s salt march, Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King Jr, and the young man holding up a column of tanks in Tiananmen Square. American writer and campaigner Rebecca Solnit argues that “what we call protest identifies one aspect of popular power and resistance, a force so woven into history and everyday life that you miss a lot of its impact if you focus only on groups of people taking stands in public places”.

Such interventions don’t always take place in the city centre, and they don’t have to involve hundreds of people. Depending on whose definition you’re comfortable with, nonviolent direct action spans a diverse field, from egging white supremacist senators to Christian activists going over the wire at the Pine Gap spy base. Transgressive acts can be crafted to ruin the media set pieces of the powerful, or physically stand in the way of unforgiveable destruction.

In modern Australian campaign folklore, the blockades of the Franklin River dam, the Jabiluka uranium mine, the Kimberley gas pipeline and the coal-seam gas exploration in the Northern Rivers Region around Bentley are standout examples of how to successfully embed these tactics within a broader strategy, but there are countless others. Take away the wide-ranging tools of direct action, and it’s debatable whether a single one of these campaigns would have been successful.

Jess Beckerling is the convenor of the Western Australian Forest Alliance, and has spent decades on the frontline of native forest conservation. “Direct action has been absolutely critical to the protection of forests in WA since the 1970s,” she says. “And without it I don’t think we’d have protected the old-growth forests.” With the logging industry exploiting loopholes in the definition of “old growth”, campaigners have again turned to direct action in Lewin forest, east of Margaret River. “People moved in and set up camp; the loggers have been pulled out. Every day since then the forest has been safe, but every day we need to be there to make sure the loggers don’t return.”

Direct action done well creates a powerful form of leverage. In the final days of the mobilisation at Bentley in 2014, I joined colleagues and friends to stand with local Aboriginal families, farmers and the wider community on a weekend when the state government was intending to send in hundreds of police. At dawn, watched over by young blockaders perched perilously above the roadway on spindly wooden tripods, we were given a brief tour of the fortifications dug into the access road on which Metgasco was demanding to move its fracking rigs. Cars were buried up to their axles in cement; welded assemblies were wired to tripods so they would come crashing down if interfered with. People were “locked on”, physically embedded in the country they were protecting. “We call it Gallipoli,” our guide informed us with a grin, as I struggled to visualise the scale of the police effort required to clear this road.

Hours later, the state government caved, withdrawing Metgasco’s licence on a technicality. The Bentley blockaders had won.

“That blockade was fundamentally local,” one organiser tells me, describing how the community shared observations about police movements. “It involved local people from across the region calling with intelligence about bookings that the police had made at local hotels. It was a genuinely society-wide response to the industry that was ultimately successful.

“One thing that direct action protest does is it creates extraordinary opportunities for people to transform their social relations. That has happened in the ‘lock the gate’ movement in a really profound way, where farmers, Aboriginal people and conservationists have made common cause. People discover when they go up against the mining industry that they have quite a bit in common with others whom they have historically, and in contemporary times, had a fair amount of conflict with.”

Sit-ins and blockades for land rights, strikes across the labour movement, the campaigns that helped form democracy and achieve near-universal suffrage, movements to end slavery and end wars: many of the rights and freedoms that some of us are fortunate enough to take for granted were won through this kind of struggle. These are some of the tactics that writer and disarmament campaigner Jonathan Schell proposed so that “the active many can overcome the ruthless few”.

In the context of a changing climate, how ruthless can they be? One example will serve. In 1977, scientists working for US oil giant Exxon provided their employer with strikingly accurate predictions of the impacts of burning fossil fuels at an ever-increasing rate. Exxon projected that carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would grow to about 415 parts per million by the year 2019, which would have the effect of warming the planet by an average of 0.9 degrees, setting off a cascade of damaging impacts. They were only two years out.

Within a decade Exxon had shut down this line of research. In the mid 1980s, internal documents showed that executives at Shell were grappling with their own studies. They wrote that “the potential implications for the world are, however, so large, that policy options need to be considered much earlier. And the energy industry needs to consider how it should play its part.”

Here’s the part they decided to play: the big five oil and gas companies now spend US$200 million a year lobbying to sabotage climate policy. They and their allies in the coal industry are reaping a stunning return on investment: the world’s governments subsidised fossil fuel consumption to the tune of US$5.3 trillion in 2015. All the while, these industries have fed the allied commercial press and the more rancid corners of the internet a fevered cocktail of denial and conspiracy. In conservative political circles, climate change has been rendered as contested or imaginary; for the truly far gone it is a sinister globalist plot to de-industrialise the world, driven by a powerful cabal of grant-seeking scientists.

The ruthless few aren’t as gormless as some of their spokespeople may appear. They wield formidable institutional leverage, and have built an architecture of industrial growth so vast that it now threatens the foundations of human society. Having accumulated this power, they have absolutely no intention of giving it up, even if it costs us the world.

The 2019 federal election demonstrates how these global dynamics work at local scales. We voted, but Clive Palmer had 60 million bucks. We wrote letters to the editor, but Australia’s largest media machine is an intrinsic part of the problem. We march, but they just ignore us until we go home.

“Unfortunately in politics, there is always a huge trend to keep the status quo. The problem is that the status quo is a suicide.”

With this casual mic-drop in June, UN Secretary-General António Guterres explained the other significant barrier to taking effective action on climate change: the challenge can feel overwhelming. The stakes are inconceivably high, and the forces arrayed against change huge.

Among those who interpret scientific research into lay language, there is a small but growing constituency who argue that we’ve already lost, and all that’s left to do is give up and brace for impact. Fed by a mix of scientific complexity and the tendency of online platforms to reward melodrama with clicks, the effect is just as demotivating as outright denial. Dubbing the phenomenon “climate doomism”, climatologist Michael E. Mann and climate-change communicator Susan Joy Hassol took a swipe at these self-appointed prophets of doom: “The evidence that climate change is a serious challenge that we must tackle now is very clear. There is no need to overstate it, particularly when it feeds a paralysing narrative of doom and hopelessness.”

Stephen Schneider, a Stanford University climatologist, put it even more simply: “Don’t exaggerate. The truth is bad enough.”

In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change issued the unambiguous warning that, while there is still time to prevent worst-case scenarios, the window is closing fast. By 2030, if we’re still on the present trajectory, the climate doomists will have the run of the table. And by all indications they’ll be completely insufferable.

Spend the 2020s continuing to transform our energy, transport, agriculture and construction sectors, and we stand a chance. If we fail, and force the planet above 1.5 degrees Celsius of average global warming, we will have committed to deeply dangerous territory. And this is no longer about the future: the damage wrought by climate change, from storms in the Sahel to melting permafrost in Siberia, is real and present.

Jim Skea, a co-chair of the 2018 IPCC working group on mitigation, made it clear: “We have pointed out the enormous benefits of keeping to 1.5C, and also the unprecedented shift in energy systems and transport that would be needed to achieve that … We show it can be done within laws of physics and chemistry. Then the final tick box is political will. We cannot answer that.”

Former slave turned abolitionist Frederick Douglass understood the answer perfectly well: “Power concedes nothing without a demand … Find out just what any people will quietly submit to and you have found out the exact measure of injustice and wrong which will be imposed upon them.”

The great question of our time is: how much longer will people quietly submit to the calculated ruination of the world? Knowingly supercharging the thermal balance of our oceanic and weather systems, and turning them against every coastal settlement on the planet, surely stands alone by any historic “measure of injustice and wrong”, but modern capitalism seems superbly efficient at adapting to and co-opting challenges to its insatiable growth program, whether they come from the ballot box or more direct interventions.

Some forms of protest have long ceased to have any impact. If what activists and environmentalists were doing worked, we wouldn’t be in such a mess. As Australian writer Kara Schlegl put it, “we’re alone in this, together … we’re losing, but we haven’t lost”, and this is causing some campaigners to question whether their tactics are still fit for purpose, or even whether some of them might have been priced into the costs of reinforcing the ever-more deadly status quo.

Direct action works best when it surprises people. “Make them stop, and reflect, and think,” one experienced campaigner says. “You can undertake direct action in a way that achieves that dynamic, but you can also undertake it in a way that just entrenches that status quo dynamic,” she warns. “That’s our challenge – to think about how to get back that sense of jujitsu. How does it throw things off balance and create the opportunity for movement in a situation that is very stultified?”

In April 2019, under the hourglass banner of the Extinction Rebellion, thousands of people swarmed into central London and Edinburgh, kicking off a rolling carnival of occupations that lasted for 10 days and resulted in more than 1100 arrests. Adept police liaisons made it clear to authorities that mass arrests were a part of the plan: with thousands of people refusing to leave, it would be up to police to manage the bottleneck of paperwork and prison overcrowding. It was the largest outbreak of civil resistance in recent memory, a major escalation of previous Extinction Rebellion actions that had been building in the United Kingdom and around the world for more than a year. Thousands of participants locked down four of London’s major intersections for more than a week, while striking at symbolic locations including the London Stock Exchange. A wave of smaller-scale actions swept across European capitals, the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and Colombia.

The demands of the UK extinction rebels were as succinct as they were ambitious: tell the truth and declare a climate emergency; achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2025; and establish a citizens assembly to oversee the changes that the parliament has failed to initiate. Immediately after staging a strategic withdrawal, to rest and plan their next move, Extinction Rebellion delegates were invited to negotiations with the mayor of London and senior UK politicians. Days later, Westminster passed a resolution accepting the reality of the climate emergency. Real policy change will be slower to follow, but it was a surprisingly rapid concession to the power of decentralised civil resistance.

Extinction Rebellion’s organising model has been the subject of much thoughtful and mostly friendly critique, with some arguing that the model constitutes a naive approach to the wisdom of mass arrests and the movement’s relationship with the police. While the strategy of submitting quietly to mass arrests and fines and legal entanglements that can spool out for months is contestable, for some communities the option is off the table. In the Australian context, contact with police and the judicial system can be unforgivably dangerous for Aboriginal people, and any social movement that centres solely on mass arrests would be problematic.

For these reasons, local Extinction Rebellion organisers are taking the time to build capacity and confidence, and are adapting the organisational culture to their specific contexts. One of the people they’ve turned to for training and mentoring is Nicola Paris, who has been running the grassroots training organisation CounterAct for more than five years.

“Direct action and civil disobedience works,” she says. “It increases risk, it can delay work at critical junctures, and damages social licence. It can reframe an issue. But it comes at a cost to some of the people who put themselves forward.

“Just in the last year, peaceful activists have experienced a growing pattern of repression that has included raids for low-level offences, record-breaking fines – including $10,000 fines for a first offence – and dangerous tactics from police.”

She warns that campaigning organisations, having spent years focusing on electoral objectives that have repeatedly failed to materialise, are now dangerously underprepared for the consequences of a surge of civil resistance that is evidently on its way. A combination of threadbare legal resources for arrestees and successive tranches of increasingly repressive anti-protest laws means that the movement needs to build capacity rapidly in order to support people who choose to risk arrest. “We need lawyers for direct representation in court, we need resources and expertise to provide activist paralegal support, and we need institutional support to challenge patterns of repression. People are also going to need longer term support and fundraising if they end up being hit by heavy fines and bail charges.”

The June 2019 federal police raids on the home of News Corp journalist Annika Smethurst and the ABC’s Sydney offices briefly focused the national media on the web of legislation empowering police and intelligence agencies to target whistleblowers, the media and other organisations. There seems little doubt that these powers will be increasingly turned against environmental campaigners as they become more outspoken and successful.

As long ago as 2017, federal MP George Christensen sought to conflate anti-Adani advocacy with acts of terrorism. “Some activists threaten lives, including their own,” he told parliament. “Such action meets the definition of terrorism in the criminal code.” While most would recoil at this hyperbole, there is no doubt that protesters and campaigners who choose to spend time on the frontline are stepping willingly into a confrontation with their own government.

Extinction Rebellion operates on a metric drawn from the research of political scientist Erica Chenoweth and policy analyst Maria J. Stephan. In their long-term study of campaigns for revolutionary, secessionist and regime-change movements from the past 150 years, they come to a few vital conclusions. First, that nonviolent movements have a vastly improved chance of success over those that pursue armed struggle or terror tactics, including under authoritarian regimes where the consequences of even peaceful dissent can be life threatening. And second, that you don’t need everybody: you only need about 3.5 per cent of the population to achieve a critical mass of sustained popular noncompliance.

Charlie Wood, who has extensive experience working with the grassroots climate movement, references this revolutionary rule of thumb. “We saw 150,000 people turn out in March for the school climate strike. Three and a half per cent of the Australian population is 860,000 people, so we have some way to go before we have reached that tipping point of people taking the level of sustained action in their communities that we need,” she tells me.

Wood knows that identifying a 3.5 per cent figure doesn’t tell you anything about how to get there, or what combination of social faultlines need to be prised open or realigned in order to trigger a sustained uprising. Nor does it tell you what happens when you hit that tipping point. Unless the demands of the movement are focused and expressed with unity, tipping points risk regressing into concessions and co-option, or violent backlash once power-holders have had a chance to regroup.

The emergence of Extinction Rebellion and the School Strike 4 Climate are important contemporary examples of protest cascades that have caught the popular imagination and grown so rapidly that those in power were caught off balance. How these movements develop from here is an open question, but in their own way they are powerful examples of how novel recombinations of old tactics can open new opportunities for mobilisation and movement growth.

Real-world social movements are fine grained, fractal and deeply human. Rather than relying on a magic tipping point, they comprise countless moments, large and small, where individual and collective decisions move political systems closer to change. Somewhere out there lies the critical mass beyond which the high-risk denial of reality becomes politically impossible. And the key to reaching that scale is to find and welcome those people who, while supportive, are yet to find a way to meaningfully join the gathering wave.

It is ironic, then, that in a deeply unexpected and backhanded way the election of an ardently pro-collapse government is driving thousands into the arms of campaigning organisations large and small.

“Since the election, Greenpeace has seen an unprecedented surge in support with tens of thousands stepping up to get involved in new ways,” chief executive of Greenpeace Australia Pacific David Ritter says. “Great change is nonlinear. History is full of pivotal moments where determined citizens have come together to drive change.”

Violet Cully, a volunteer with the AYCC, also takes heart from the surge of new supporters: “There has been this massive influx of people that signed up the day after the election. It’s amazing to see how many young people are fired up about this.”

Charlie Wood, welcoming the influx of people looking for ways to make a contribution, is cheerfully determined to make the most of it. “I’m feeling emboldened. Whatever the outcome, I feel we were going to have our work cut out for us in raising political ambition. History shows us that politicians seldom lead: powerful social movements have to push them to catch up.”

Along the way, these movements need to take care of the people who show up and link arms. Caz Chattin is a key coordinator with Extinction Rebellion Sydney, which is in the process of scaling up to undertake acts of greater visibility. It’s the first time she’s taken on anything like this before, and I ask what it is about the organising model that attracted her.

“We’re using the regenerative culture part of Extinction Rebellion – the idea that we all take care of each other. In the UK they’ve had a massive win; they’re having a rest now. They’re still doing things, but taking a little bit of a break to not burn out,” she says.

Cully from the AYCC agrees, adding that simply spending time in the company of others who had chosen action over despair had changed her life. “Before I joined AYCC I felt powerless; I didn’t think that government and people in power were doing anything to solve these issues. I didn’t know that we could have the power to change things.”

Wood ponders how to take emergency-scale action that reflects the scale of the crisis while staying true to the deeper implications of climate justice. “There is certainly no justice in acting at the pace that we’re currently acting: we need to be acting at a pace that is commensurate with the crisis. Making sure that action is centred in justice, that it’s led by First Nations people and those who will be most directly impacted by the crisis – those on the frontlines of climate change and fossil fuel extraction. I don’t see those things as being in opposition.”

We may at last be past the stage where climate action is promoted as nothing more than changing your soft drink or taking the bus once a week. At worst, some forms of green consumerism signify little more than the commodification of resistance itself, as if the revolution is just a few virtuous purchases away.

American writer and speaker Alex Steffen comes down hard on the demobilising impacts of such privatised solutions. “We tell people the truth – that an ecological collapse is on its way, and that avoiding it demands widespread transformation – and then we suggest that they take some small steps whose meaninglessness in the face of massive crisis is self-evident. We ought instead to ask from them, and demand from ourselves, action commensurate to the crisis, which is to say heroic action.”

In that narrow space of light between denial and defeatism, staring down the most powerful institutions in the world, stands a Year 12 student with a placard on the steps of the Victorian parliament. Behind her are classmates from every time zone on the planet; kids with names she’ll never know, from London and Seoul to Cape Town and Mumbai. Beside her are extinction rebels, forest protectors, anti-fracking organisers, anti-coal activists. All around her are First Nations warriors, teachers and elders who have been fighting mass extinction, violent inequality and environmental collapse since 1788.

The UK, home of the industrial revolution, keeps extending the record for the number of days it runs without coal. The German government recently agreed to an accelerated phase-out of coal and an ambitious roll-out of renewable energy. In the wake of the 2011 Fukushima disaster, Japan is now constructing an unprecedented number of solar fields. Across the Global South, renewable energy offers the promise of locally owned, appropriately scaled energy networks that will leapfrog the 19th-century infrastructure of the “developed” world entirely. With the seismic realignment of energy economics comes the dawning realisation that this is about much more than energy: it is about power.

Jai Allan Wright has a message for those filing into Australia’s 46th parliament against a backdrop of darkening skies: “If you can’t do the job, if you’re not willing to do what it takes to reach the solutions that we know we have to enact, to meet the challenges of a climate crisis, then you shouldn’t be there. Step down.”

In showing up for the fight in this crucial decade, this growing civil resistance is buying time for the engineers, the planners, the architects, the diplomats and, yes, the politicians, to do their fucking jobs: to turn the ship of state before the damage is irreversible. Nobody knows if this re-energised global movement will hit critical mass in the time we have left, but to those lending their strength to the next crucial stage of organising, the company they keep is reward in itself.

“You’re not alone,” Nyah Shahab says, before grabbing her bag and heading back out to finish her exam prep for the day. “Before I got involved in the strike movement I was constantly overwhelmed with the feeling of anxiety about climate change. But if you look around, just look at how many people care and how many people aren’t going to let this continue to happen.”

This is the generation that is choosing not to accept the theft of their future gracefully. They’ll be less activist when things are less shit.